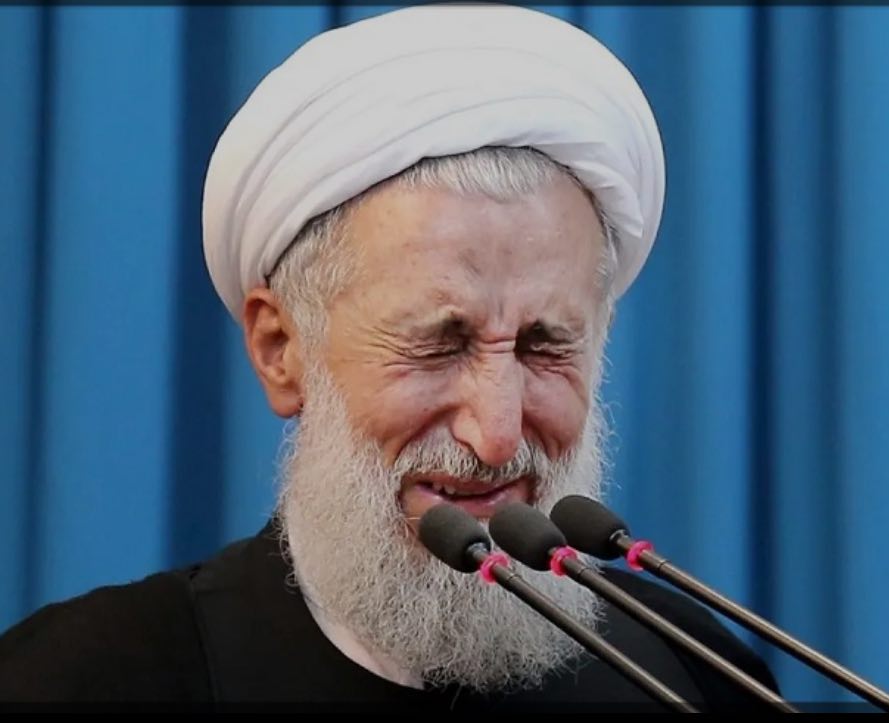

Economic Corruption of Tehran’s Friday Prayer Leader

The Spiritual Yield of the Cherry Orchard for Sedighi

Although we have previously addressed the economic corruption involving the Tehran Friday Prayer Leader, the story is as follows: a 4,200 square meter orchard belonging to a seminary under Mr. Sedighi’s administration was transferred to an institution owned by him and his family. Initially, it was claimed that his signature had been forged, but it was later revealed that he was present as both the seller and buyer at the notary office, with his fingerprint also confirmed. A document was even published showing that a cash payment had been made.

In a subsequent statement, it was said that he had not read the statute and had trusted others, which was exploited. However, no news of a complaint against the forger was released. Instead of apologizing to the public, they asked for prayers and also sought forgiveness, although they attributed it to enemy conspiracies and foreign media. Amidst these discussions, it was announced that Mr. Sedighi would be one of the speakers for the Night of Power at Imam Sadegh University. The negative reactions on social media were such that the organizers, fearing protests at the venue and the overshadowing of religious aspects, announced its cancellation.

This piece is, of course, a note, and the events are reported. The introduction is merely a prelude to the lessons of this story, which includes various and numerous points.

The first point is that what an investigative journalist managed to accomplish might not have been achievable by official institutions with large budgets. Even if the claim that the whistleblower had special connections or received information from certain places is true, it does not affect the core issue. The main point is that the more opportunities for information dissemination and independent investigative journalism, the less corruption there will be. One cannot claim to fight corruption while simultaneously restricting the press.

Second, the issue has been questionable from the start. From the time the cherry orchard was destroyed and the change of use was approved, the seed of misconduct was planted. If there had been sensitivity about this 20 years ago, the subsequent events might not have occurred. In similar cases, such foresight should be considered from the beginning. Changing the use of a cherry orchard under the pretext of establishing a seminary and later transferring part of the property to an institution or private individual should be anticipated.

The explicit support of the Tehran Municipality newspaper, which called for a faithful approach, and the recent remarks of the head of Channel Three confirm that without media monopoly, exposing this misconduct would not have been possible. This is the third lesson: one cannot expect official and promotional media to be sensitive to such matters. As Dr. Shariati puts it, to understand how someone thinks, one must know where their funding comes from.

The fourth lesson is that just as scholars take a stand against usury, they should also express sensitivity towards hypocrisy. Although not all of Mr. Sedighi’s actions can be deemed hypocritical, the public feels that there is a disconnect between what he said and the tears on his face and what actually happened.

The fifth lesson of this tale is that limiting the promotion of virtue and prevention of vice to the clothing of women and girls is far removed from public perception. What has happened now is that what the head of the promotion of virtue and prevention of vice committee has done is considered by society itself as an example of vice, as he explicitly admitted to negligence and sought forgiveness.

The real promotion of virtue is precisely what the media and critics did in exposing this story, without receiving a penny in funding, unlike the committee under Mr. Sedighi’s direction, which claimed to do so with substantial budgets and resulted in heavy political and social costs. With existing anti-corruption laws, this is commendable, not condemnable.

The sixth lesson is that religious leaders should be more vigilant about their children, as not much time has passed since the issue of the former first deputy of the judiciary and his children’s case. In Mr. Sedighi’s case, it’s likely that his children were concerned about their future after their father and wanted to ensure they received a share, leading them to establish an ostensibly cultural institution with commercial aims, possibly eyeing the future sale of property and planning for migration.

Typically, someone close to these children takes over and advances the project. Given this experience, it’s better to steer their children away from hovering around their father and towards real education or business.

Let’s remember that in his first interview with TV reporter Yousef Salami, Mr. Sedighi recited a verse from the Quran reflecting Jacob’s complaint about his children: ‘I only complain of my suffering and my grief to Allah, and I know from Allah that which you do not know.’ This event was also a test for radical Iranian conservatism, which claimed to fight corruption and discrimination during the reform and moderation eras, and by supporting or trying to justify Mr. Sedighi’s actions, showed how genuine those claims were. This is the seventh lesson.

From another perspective, it can be noted that the clearer and stronger a person’s background, the less likely they are to make such mistakes, as they value their brand and don’t want to damage it. However, Mr. Sedighi had no significant background in the 1979 revolution, and although at that time, when young people aged 18 to 30 were leading, he was 27, which was not too young to be known as a revolutionary cleric, he was not recognized with such a title. This absence or deficiency might have led him to overlook certain points, and this is the eighth lesson: to assign major tasks to those with a background.

The potential separation of Mr. Sedighi from Tehran’s Friday prayers might also alleviate concerns for worshippers who attend for purely religious reasons, as the sermons are considered equivalent to two units of prayer, and the interim Friday prayer leader, by admitting ignorance and negligence, may have disqualified himself from the condition of justice.

In this view, the Friday prayer committee should reduce its political intensity and pay attention to the interests of purely religious and less governmental and political groups, as they have been hurt by the recent incident. The ninth lesson could be this, although from the positions of other Friday prayer leaders and their silence on this issue, it can be concluded that this lesson has not been widely learned.

Regarding the incident and the alleged misconduct or crime, there is no consensus. Accusations range from land grabbing to acquiring illegitimate wealth and breach of trust. Since each carries its own legal weight, the author of these lines insists on none but suggests asking judicial authorities what exactly this action can be called if they consider it criminal, and if not, why the perpetrator seeks forgiveness.

In the West, which we constantly criticize, especially Britain, which is more based on tradition, when something like this happens, they enhance their legal richness. However, in this interval, apart from lawyers’ opinions, we haven’t seen a judicial stance, as if the memory of those five or six years when Mr. Sedighi was the head of the Judges’ Disciplinary Court and their hands were under his ruling has not faded. Although this can be a reason to question cases he may have recommended.

Although this revelation is the result of a media activist’s efforts, with the registration of individuals’ national codes, notaries and agencies can also relay information in similar cases, and this is not only not reprehensible but commendable, as the information is neither classified nor secret. Based on what Mr. Foroughi from Channel Three or others have said, it’s likely that this information leaked from within Sedighi’s seminary. In fact, one can say if we criticize their flaws, we should also acknowledge their merits, and this merit is that among those students and nurtured individuals, there were those sensitive to public assets who valued their doubt more than Mr. Sedighi’s tears.

Finally, apart from these points, which are not without some jabs to reduce the political burden, we can turn to the most serious lesson and insight, as perhaps the damage that Shia clergy have suffered or accepted from this incident is incomparable to any other blow.

It’s true that historically, Shia clergy have interacted with the market and business and have dealt with land and property more, and so far, nothing new has happened. But the fact that part of the public assets belonging to a seminary is transferred by its administration to a family institution is not compatible with this background and has no reason other than the merging of religion with power and politics. This is just one of the consequences and pitfalls of this issue that has emerged.

In Iranian culture, the disgrace of encroaching on assets or properties belonging to religious and public places is such that we are all familiar with this proverb:

The one who steals the breeze is a thief, the one who steals the carpet from the Kaaba is a thief.

God forbid, we do not wish to accuse Mr. Sedighi personally, and we take his claim of negligence and ignorance as true. However, this act, regardless of the doer and their knowledge or ignorance, of transferring the seminary’s orchard to oneself or another in one or two stages can be a clear example of stealing the carpet from the Kaaba.

Both those who advanced this project and Mr. Sedighi himself were aware of this, as the former acted under a pre-seminary and cultural guise, although not mentioned in the statute, and the esteemed administration, who played both seller and buyer roles, assured that the seminary’s assets were never exposed to transfer with the establishment of the institution.

Of course, a witty person asked if the property was not exposed to transfer, then what was it exposed to, or what was exposed to transfer, and how can the event that occurred be explained? One can only hope that the carpet returns to the Kaaba, although in this case, the analogy and metaphor to the Kaaba are not appropriate, as there are many stories about the original tale.