Tataloo, the Alarm and Warning Sound from the Society’s Underground

Tataloo, the alarm and warning sound from the society’s underground, was born, grew, and emerged from the underground. Before becoming a singer, he was underground, and his personality can be seen as a concentrated symbolic output of the impact of social harms on an individual.

Many grew up in poor neighborhoods, some of whom continued their lives on a horizontal line, and no one asked about their fate, whether good or bad. However, some people from there managed to lift themselves up at least a little, despite all the difficulties, and tried to ascend culturally and class-wise, if not possible, at least climb a few steps. Here, however, we are talking about those who remained in the lowest class of society, and their efforts to rise only bring a thick and unpleasant aroma, an essence of the infections of the black hole, to the surface of the city, irritating the noses of the stylish people on the ground.

One of those who snatched phones said he sometimes earned up to 15 million tomans a day. You can also find plenty of muggers and hired bullies from those damaged layers of society, whose weekly income sometimes equals or even exceeds the six-month salary of a middle-class employee, yet they remain in the same underground class.

They earn all this money but never become wealthy, and if they abandon such lucrative activities, a month later they can’t afford a few loaves of bread. It’s as if a cultural rope ties them to a post underground, preventing them from rising economically, even if they become wealthy, their social and cultural class likely wouldn’t change.

Analyzing this group is extensive and has its complexities, but almost everyone agrees that if these people were born and raised in another class of the social building instead of the underground, the likelihood of them developing such personalities would be reduced to one-thousandth.

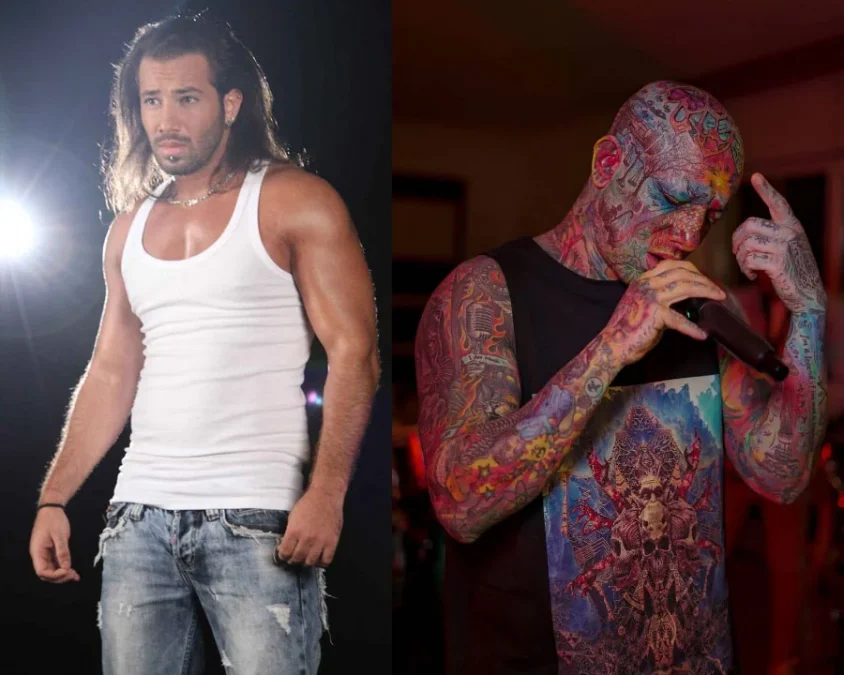

Amirhossein Maghsoudloo, or Tataloo, is one of the children born in the society’s underground building and remains underground. The story of Amirhossein turning into Tataloo is the tale of the unsuccessful efforts of one of the underground kids trying to rise from his class and reach the surface.

He tried to become a singer for his generation’s youth in the middle class and even sang for the green candidate during the tumultuous year of ’88. But gradually, he became disillusioned with this effort, and his relationship with the middle class turned into a rivalry and challenge.

Amirhossein Maghsoudloo wanted to be reborn, this time in the middle class, but when he realized this was not possible for him, he used all the tricks he learned underground to challenge and annoy the middle class, and through this, he managed to achieve some success.

Now he had become a joker who, failing to gain the favor of his middle-class peers, managed to rally a legion of teenagers from later decades to support him, and in this way, Tataloo was born.

Tataloo’s attack on the values of the middle class, extending from personal freedoms to symbols like Mohammad Reza Shajarian, was not at all justice-seeking but a product of injustice. He said whatever he wanted, right or wrong, with a biting and often obscene tone, becoming an unrivaled master at irritating the middle class.

This personality style actually greatly helped his fame, and the fact that the more the middle class got annoyed with Tataloo, the more famous he became was itself a phenomenon that could be viewed and analyzed from a new angle, especially in the age of social networks.

Tataloo’s personality was essentially born out of rivalry and stubbornness with a class that did not accept him and in every encounter with this underground boy, held their noses with a handkerchief and passed by. At a time when almost all Persian songs, if not joyful, had themes of heartbreak or so-called romantic failure, Tataloo’s theme was that he was outsmarted but ultimately won the fight. This too rose from that constant rivalry, similar to the final dialogue of the movie Papillon, where Steve McQueen, when he finally escapes from the Guiana prison and jumps into the sea, shouts, ‘Hey, bastards, I’m still alive.’

Tataloo also directed this shout at those he saw as his jailers in the underground, the same middle-class people who wouldn’t let him rise and become like them, from Mrs. Vaziri in his song to Master Shajarian in his always controversial interviews. He constantly shouted at any character from the middle class he felt wanted someone like Tataloo or Maghsoudloo not to exist, with different tones, that hey, this mad rivalry eventually fell into the trap of politics too.

Tataloo made efforts to whitewash himself, and some political movements thought they could use him as a symbol of their tolerance on one hand and a symbol of the open door of repentance for everyone on the other. After the 2017 presidential election, Amir Tataloo and Sasi Mankan became mass symbols for the two main political factions in the country.

Tataloo’s case was entirely clear, but the opposing faction, which advanced with Sasi, as always, behaved ambiguously. Despite having the most share in government positions throughout the years after the revolution, at some point, they tried to present themselves as independent from the government.

For example, instead of funding cinema through Farabi and similar institutions to make their desired films, to escape the stigma of being governmental, they allowed some individuals to embezzle from banks, financial institutions, and pension funds. Such individuals introduced dirty money as private investment into cinema and the home video network. If someone saw these individuals with their purchased celebrities in the campaign of a particular presidential candidate, they supposedly had to accept that this was personal behavior, non-commissioned, and voluntary, and the stigma of being governmental didn’t stick to it.

The amplification of Sasi Mankan against Tataloo by that political faction was done in this ambiguous way, similar to the governmental wheat-sellers claiming independence from the government. Sasi Mankan’s obscene music gained significant attention over several years just because videos from elementary schools were released showing children singing along to these songs, while the cameraman for all these selfie videos was the class teacher. Supposedly, we had to believe that everything was done in the private sector and the Ministry of Education hadn’t deliberately left a corner of the door open for this cold to enter the room spontaneously.

There is an Iranian saying with the gist that the snake tells the bee, ‘You sting, I’ll show myself,’ and the issue of amplifying Sasi Mankan with school videos and the relation of this matter with the government at the time was an example of this saying. The point is, whatever Sasi Mankan did, it was ultimately critiqued and never became publicly hated by the middle class because the amplifiers for him were from another political faction.

In any case, Tataloo was much more successful than Sasi in attracting audiences, and at the same time, his relationship with that political stream he had associated himself with didn’t remain without challenges. That mad rivalry with the middle class gradually turned Tataloo into a complete madman. One day he insulted the third Imam of the Shiites, and the next day he apologized and released a video where a local eulogist said Amirhossein Maghsoudloo had funded a religious gathering.

One day he talked about how women shouldn’t work and socialize with men, and the next day he issued an Instagram announcement accepting volunteers under 20 years old to join his harem. The more the crowd got irritated with Tataloo’s actions, the more infuriating his responses became.

For instance, when attacked about the audacity and obvious immorality he was committing, he responded that young virgins should bring consent forms from their parents to join his harem so the issue would be unobjectionable. He had become a monster, and those he was irritating were no longer just the middle class; anyone from any class who had an ounce of commitment to ethics and norms was outraged.

By now, Tataloo had turned into a dangerous infection. He held concerts and in the middle said, ‘Wait a few minutes while I go do drugs and come back.’ At the same concert, he constantly insulted his fans, and the whistles and claps of fools who heard the insults and got excited irritated the sensible and ordinary people of society, not just the red, green, purple, pink, and gray middle-class people.

Tataloo’s harem finally got him into trouble. He could have had numerous sexual relationships in Turkey without anyone getting much wind of it or becoming sensitive, but he deliberately issued announcements and even pretended to do more than he did to irritate and be seen.

Tataloo was the voice of the depths and for a long time used the irritation of the middle class to break the invisible barrier of being unnoticed, but he continued this method to such an extent that it led to him clashing with the most basic human principles and sinking into filth. He has now reached a point and done things that no person with common sense and logic can defend, and ultimately, one can only count on the support of the irrational and illogical crowd to fill a concert hall, nothing more.

But let’s review up to this point how this underground boy passed by several of us middle-class people on his journey so far and how much opportunity each of us had to prevent him from falling onto the track of becoming a monster, from the green campaign headquarters in ’88 to meeting with the chief justice in ’96 and after that attending the Fars News Agency celebration.

From being on a navy ship and singing for nuclear energy to singing in solidarity with the 2021 protesters, from the football field to cinematic contexts, from cafes to mourning gatherings, he chased us everywhere to be accepted. He chased our religious figures, chased our intellectuals, took photos with our clerics, became housemates with our movie stars, and in short, did everything to be accepted, but we, who repeatedly took positions at various political and social turns and fired shots at each other, were united and in agreement in rejecting this underground kid.

Sometimes, if he was useful to us, we tried to use him, like in the years ’88 and ’96, but ultimately returned to previous settings and distanced ourselves, pressing a handkerchief on our noses so we wouldn’t catch his underground scent.

Tataloo was not a justice-seeker but a product of injustice. Perhaps this dirty monster wouldn’t have become what he is today if someone had thought a little about him instead of just themselves. Monsters must be punished, but we never see in any part of history that those who could have prevented the birth of a monster and didn’t are punished, and what can be done, this is one of the tragic aspects of human life.