The Relationship Between Liberalism and Reformism

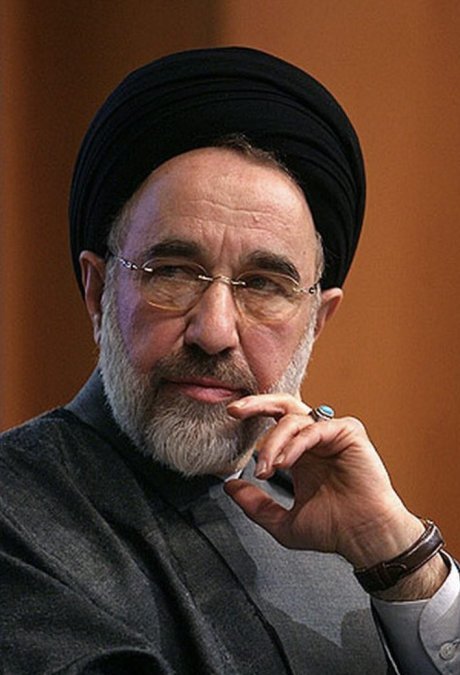

According to Iran Gate, although Mohammad Khatami considered liberalism incompatible with Islam, both his opponents and supporters viewed his reform project as one aimed at political and social liberalization in post-revolutionary Iran. Conservatives saw Khatami as a liberal dressed in clerical attire, and voters mostly expected him to realize liberal freedoms.

By the end of the reform era, no one could unravel the enigma of Khatami’s rejection of liberalism, nor understand why, if liberalism was incompatible with religiosity, Khatami’s political slogans all had a liberal hue and scent.

Liberalism emphasizes the distribution of power, knowledge, and prestige, ideological tolerance, the clash of opinions, legal equality of citizens, individual freedom, natural human rights, and political and religious pluralism, all of which were clearly observable in Khatami’s words and deeds.

If until the early 1990s, trade was monopolized by the traditional right, the modern right emerged during Hashemi Rafsanjani’s presidency, led by the Executives of Construction, to break the monopoly of wealth held by traditional right-wingers. While the radical right opposed tolerance, legal equality of citizens, and religious and political pluralism, the Kian and Ayeen circles were working to theorize and operationalize these concepts.

The Executives of Construction, Kian, and Ayeen were among Khatami’s allies and pillars of his government, yet Khatami and his entourage were cautious about being labeled as liberals. Most of the rejected bills of the Sixth Parliament had a liberal orientation, but neither Khatami nor the reformist parliament members wanted to call themselves liberal. In the first half of 2001, Mohsen Armin emphasized the democratic nature of reformist demands and noted that reformists were not seeking to realize liberalism in Iranian society.

Armin’s statement prompted Akbar Ganji to remind that all the desired goods of reformists can be found in the market of liberalism, and if this is the case, why not openly and comfortably declare themselves customers of this market? Were the reformists practicing dissimulation when they distanced themselves from liberals, or was there another reason that led reformists to adopt the cup of liberalism but not its name?

If we only seek the reason for reformists’ reluctance to use the term liberalism in their political caution, it all goes back to the political literature of Iranian society. The forty-year effort of the Tudeh Party to discredit liberalism in Iran undoubtedly played a fundamental role in the reformists’ dissimulation and caution.

In the Tudeh Party’s literature, being liberal and being an imperialist lackey were synonymous. After the revolution, liberalism in the writings and speeches of Muslim revolutionaries in Iranian society meant nothing more than being an American lackey, an imperialist agent, an oppressor of the underprivileged, and a hedonist.

Unfortunately, a significant number of those who fueled such rhetoric in the 1980s were Muslim leftists who became reformists in the 1990s. It was obvious they couldn’t adopt the same name and title they had used as an insult for years. But this was only part of the story; the main issue lies in the reformists’ uncertainty regarding liberalism.

For instance, in the early 1990s, Abdolkarim Soroush, while stating that the components of liberalism complement each other and having some without others would create a hybrid society, also emphasized that not submitting to any authority is an essential and fundamental element of liberalism. Yet, when determining how to implement liberalism in a religious society, he advocated for adopting some elements of liberalism and leaving others, and he said that questioning the principle of religious authority enters the deepest realms of liberalism. However, liberalizing the economy and government is something that can be discussed within a religious society.

Although Soroush became more liberal over time, and by the late 1990s, in discussing the relationship between religion and liberalism, he noted that liberal societies, with their inquisitive and experiential spirit, are more rational than religious societies. Yet, he still correctly emphasized that a religious society cannot accept every form of liberalism.

In parentheses, it should be noted that a religious society is different from a society where religiosity is free. The latter is a liberal society. The source of the reformists’ uncertainty regarding liberalism stemmed from the concern over which form of liberalism the religious society of Iran, transitioning through the broad path of liberal reforms, should accept and choose.

Furthermore, although reformists sought to liberalize the state and society of Iran, they were also wary of completely liberalizing the social relations and atmosphere of Iran. They were concerned that if liberalism entered entirely, the realization of liberal freedoms in post-revolutionary Iran might push the social atmosphere towards moral recklessness and the political atmosphere towards the realization and dominance of secularism.

In other words, they were worried that in aiming to establish religious democracy, they might implement liberal reforms in Iran, but the final destination of these reforms might not be religious democracy but secular democracy. Therefore, they cautiously avoided engaging in moral liberalism and considered theorizing it as paving the way for the secularization of Iranian people’s behavior.

Thus, it is not an exaggeration to say that the reformists’ liberalism was incomplete. They intended to liberalize some political, social, and cultural relations in Iran, but they did not want to transform a religious society into a liberal one. As Soroush himself said, liberalizing the economy and government within a religious society is possible and has nothing to do with liberalism in its complete and philosophical sense.

The reformists’ uncertainty regarding liberalism was so pronounced that Hossein Marashi described the Executives of Construction as a Muslim liberal-democratic party, but Khatami at the same time called liberals the main obstacle to reforms. From Khatami’s perspective, reformists were not true liberals; he explicitly stated that the philosophical foundations of Islam differ from liberalism. How can a true Muslim be a true liberal?

Khatami’s explanation regarding his liberal slogans was as follows:

Freedom means the right to self-determination by humans, the foundation of power on the free will of the people, and respect for freedom of thought and expression. As a Muslim, I am proud to adhere to these. I accept that Islam. If this is liberalism, then it is very good. In reforms, emphasizing and supporting fundamental freedoms in society and defending the people’s right to self-determination is a fundamental principle. Accusing those who talk about freedom and defend people’s rights of being liberal and promoting liberalism is a significant deviation.

Khatami was also proud that the most extensive and scientific critiques of the philosophical foundations of liberalism were conducted by many reformists, including himself. Thus, throughout the reform era, reformists could not determine exactly what their relationship with liberalism was, and as a political sociologist put it, they were caught between modern and traditional values.

They accepted parts of liberalism and rejected others, but it seemed they themselves were undergoing a process of transformation and conversion, which was why they became more liberal from 1997 to 2005. However, liberalism ultimately became a weapon for them to combat the right-wing faction. Their liberalism was much more prominent in opposition to this faction than when confronting secular intellectuals and politicians outside the Islamic Republic system.

In opposition to these individuals, reformists would lower their liberalism flame and emphasize the religious nature of Iranian society, a story that continues to this day, with its most recent manifestations evident in Abdolkarim Soroush’s critiques of the secular opposition abroad.

English

View this article in English