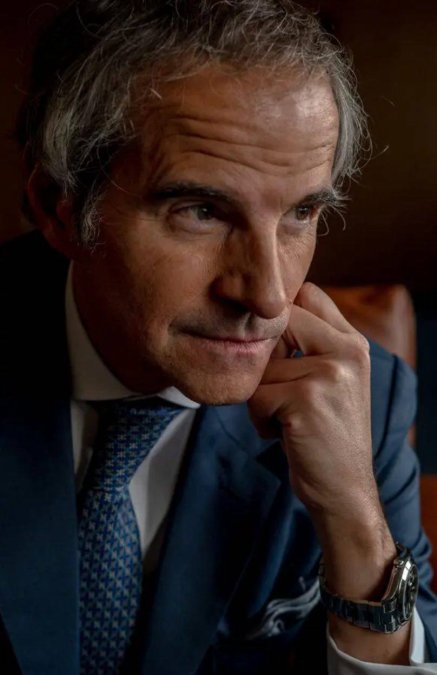

The head of the UN nuclear agency, Rafael Grossi, says, ‘I am a calm person. I focus on the things I can do.’

The head of the UN nuclear agency, Rafael Grossi, says, ‘I am a calm person. I focus on the things I can do.’

Rafael Grossi, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which is considered the world’s nuclear police, taps two points on a white napkin with his knife. ‘This is Moscow,’ he says.

‘This is Kyiv,’ he continues, moving his hand between the two and marking Zaporizhzhia, a massive Ukrainian nuclear power plant. This plant once supplied a fifth of the country’s electricity but is now occupied by Russian soldiers and has become one of the first civilian nuclear power plants to be attacked in war.

‘Currently, the bombings there have increased significantly, and the Russians are exerting a lot of pressure,’ Grossi says, explaining that a rotating team from the IAEA has been present there since 2022 to prevent a disaster similar to Chernobyl.

‘It’s dangerous, but we have to be there,’ he adds, revealing that he has traveled there five times himself, under direct fire.

As I listen to him, I feel a cognitive dissonance. We meet in the restaurant Sacher, one of Vienna’s luxurious restaurants, a place where the chic streets filled with sunlight and the sound of old clock chimes give a sense of timeless calm.

Yet, 64-year-old Grossi is grappling with something that casts a shadow over all of us, even if we usually ignore it.

As depicted in the bestselling book ‘Nuclear War’ by Annie Jacobsen, this is the danger that an accidental or deliberate nuclear disaster could, at best, contaminate areas or, at worst, destroy civilization.

This is part of the concern that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has put civilian nuclear power plants at risk, while Vladimir Putin has repeatedly threatened to use nuclear weapons.

‘It’s concerning because it normalizes the issue,’ Grossi acknowledges shrewdly.

‘In the past, this was taboo, but now people talk about tactical nuclear weapons as if it’s something that can be limited or allowed.’

Grossi is also dealing with nuclear North Korea, rising tensions between India and Pakistan, both nuclear powers, and his greatest concern, Iran. According to a new and confidential IAEA report, Iran has significantly increased its stockpile of near-weapons-grade enriched uranium, while Israel has threatened to attack.

Earlier this year, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists announced that the world is now only 89 seconds away from midnight on the Doomsday Clock. But there is also a deep contradiction: just as these existential threats worsen, Grossi is witnessing increased interest in nuclear energy production as policymakers recognize that it could be a green and strong source for digital technology.

So, while nuclear energy carries enormous risks, it also offers extraordinary promises. Which of these paths will be chosen now with Grossi’s diplomatic skills and our political leaders?

So, as we sit down for lunch, I ask him if he’s scared of this responsibility. He shrugs and leans in, ‘I am a calm person.’

‘I focus on the things I can do.’

He chose the restaurant because he likes the nearby opera house, and its Italian cuisine aligns with his heritage. Although born in Argentina, his family is from Italy, like more than half of Argentina’s population.

This shows a slender man, Grossi, wearing a suit in the sleekest Milan style, with bracelets from the 2022 World Cup in Qatar under his sleeve.

‘He’s crazy about football,’ he explains, and after watching Argentina’s victory there in penalty shootouts, ‘I won’t miss them until the next World Cup.’

I ask him what happens if Argentina plays Italy. ‘It’s Argentina,’ he says, ‘but otherwise, I support Italy,’ Grossi says, who speaks Spanish, Italian, and four other languages.

In all other aspects of life, however, he strives to be non-tribal, as expected of a professional diplomat. After studying political science, he represented Argentina in numerous missions, including serving as the chief of staff at the IAEA and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

Then, in 2019, he became the sixth Director General of the IAEA, a UN agency since its establishment in 1957, overseeing about 2,500 employees.

He is set to be at the IAEA for a few more years, but he tells me he intends to run for UN Secretary-General when the post becomes available next year. He says, ‘I’m not going to campaign; my work is my campaign.’