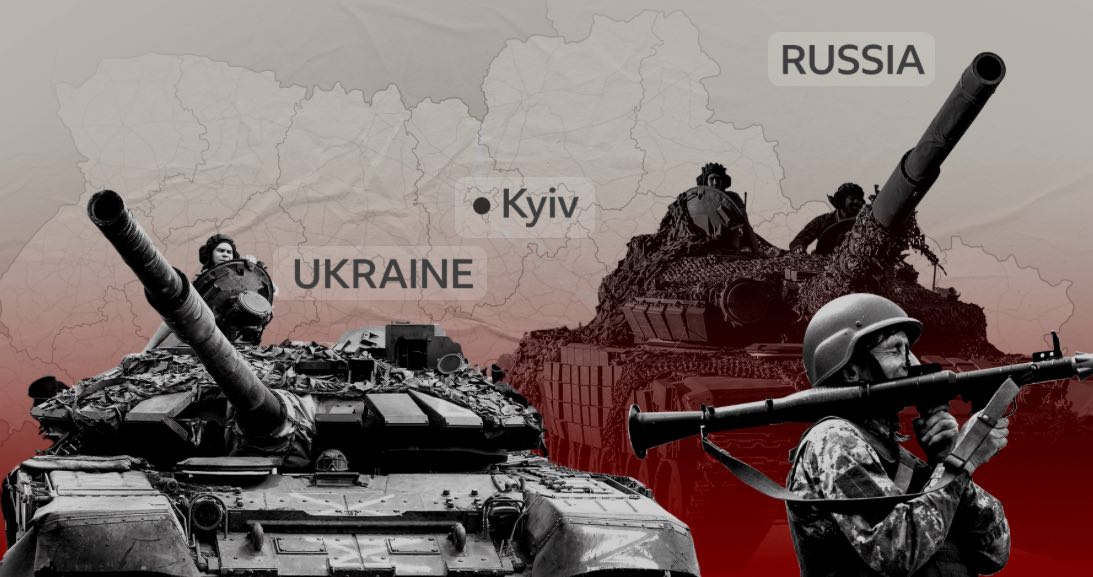

A Look at War-Torn Russia from Within

A Look at War-Torn Russia from Within

When Kirill Babkin was younger, he and his siblings became orphans after their alcoholic mother was stripped of her parental rights.

Last spring, after his mother died in a house fire, 19-year-old Babkin volunteered to participate in the war in Ukraine, signing a contract that promised a very high salary to support his surviving siblings.

He was killed in Ukraine last September and was buried on December 11 in Yelabuga, Tatarstan, the same place where Russia, with Iran’s help, produces Shahed drones to destroy Ukraine’s civilian infrastructure. When his obituary and tragic story were published on the social network VKontakte, readers expressed their condolences and shared their opinions on the developments in the war.

A person named Ildus wrote, ‘I feel sorry for his brothers and sisters. He tried to give them a comfortable life.’

This is very painful and tragic. However, another person responded to this message, writing, ‘He took up arms for his family’s comfortable life to go to a foreign country and take the lives of its people. Truly sorry.’

Such reactions, as the full-scale invasion of Ukraine nears the end of its third year, open a small window into the significant changes in Russian society. Vladimir Putin’s increasingly authoritarian rule has stifled protesters and political opponents, criminalizing criticism of the armed forces or even candid discussions about the war’s nature or meaning.

The suppression of any voice not in alignment with the Kremlin has made the work of sociologists, polling centers, and journalists seeking the opinions of ordinary Russians, especially in areas far from Moscow and St. Petersburg, difficult. In recent weeks, independent journalists have interviewed dozens of people, mainly in Tatarstan and Bashkortostan—regions that have sent the most manpower to the war and suffered more casualties than other parts of Russia. These interviews were conducted via encrypted messages on social networks to avoid punishment and threats from security services, with all names changed.

Irina, a 52-year-old social worker from Ufa, says, ‘If we want to talk about the war and its impact on each of us and our country, I can say things are getting worse and worse.’ She added, ‘The war is getting closer, and the fear of it has become widespread.’

Of course, this fear increases the hope that those who have not yet grasped the depth of the disaster will eventually wake up. Alisa, a 30-year-old who promotes a commercial company based in Samara on social media, wrote in response to reporters’ questions about the war’s impact on her daily life, ‘What can I say? I no longer follow the news. It’s a defense mechanism to continue my seemingly normal life in these disastrous conditions.’

Russian authorities do not publish war casualty statistics.

In the list of war casualties compiled jointly by the Russian section of the BBC and the Meduza publication, the names of over 90,000 people are mentioned. Western intelligence officials estimate Russian military casualties to exceed 700,000. A British official predicted that by next autumn, the number of Russian soldiers killed and injured on the Ukrainian fronts will reach one million.

Estimates from independent media identify Tatarstan and Bashkortostan as regions most affected by the war.

Erik, a 55-year-old working for a cultural institution in Ufa, says the voices of those remaining in Russia have increasingly been silenced. According to him, many Russian citizens have chosen to remain silent and do not express their thoughts at all.

But one cannot ignore the disabled individuals in military uniforms walking with canes or in wheelchairs on city streets. Cemeteries are filled with flags placed on new graves.

Chinese Cars, Old Appliances, and Iranian Coca-Cola

In previous years, Russia’s economy significantly focused on strengthening the middle class, but after the start of the war against Ukraine, the military industries have become the engine of the economy.

Moreover, Western sanctions have put pressure on employees and entrepreneurs, disrupted trade relations with Europe, and forced many companies to change trade routes to the south and east. Those who spoke to independent journalists acknowledged that everyday problems are increasing.

Many of them expressed surprise and regret that instead of the products Russians had become accustomed to in recent years, they now have to deal with Iranian Coca-Cola and Chinese cars. However, Denis, a 45-year-old researcher at Ufa University, says Russian citizens look to the future with hope and are optimistic about the country’s economic resilience. According to him, the blows of the war have become background noise for many people.

He further explains, ‘I can’t buy Italian clothes, I can’t fly to Barcelona for the weekend, I can’t buy a European car, or rather, I can do all these things, just much more expensively than before.’ Denis added, ‘Now instead of Barcelona, one can travel to Bukhara, for example, an ancient and very beautiful city. However, the flight to Bukhara is three times more expensive than the ticket to Barcelona.’

Erik went on to mention numerous cases of exploding Chinese cars that have replaced Western brands and added that Chinese cars are disposable and will likely become a serious problem for us in the future because repair shops currently cannot handle the volume of problematic cars. According to Erik, Chinese phones are the same.

He also reported on the boom in appliance repair services, explaining that people are now more likely to repair old appliances and buy new ones less frequently. Meanwhile, in Tatarstan and other provinces, volunteer soldiers who have received financial rewards for signing contracts with the Ministry of Defense and fighting in Ukraine, or the survivors of those killed, are making money hand over fist. In some areas, large purchases have caused a flood of money and boosted the local economy. Larisa, a 28-year-old working in the cultural department of Samara’s government, says, ‘I can’t say the standard of living has dropped. On the contrary, in some areas, the minimum wage has increased, but with this salary, you can’t leave the country, even if you want to.’

For Rustam, a 27-year-old computer programmer from Saratov, the biggest problem last year was the blocking of YouTube and Discord. He says, ‘In 2024, I upgraded my computer and bought a new TV.’

But inflation has become severe, interest rates have risen, and the value of the national currency is decreasing daily. These developments affect the standard of living, though not to the extent that I would fall into poverty or go hungry.

In Samara, like other large and small cities in Russia, wherever you look, you see advertisements for the duty of a patriot along with the rewards for volunteer soldiers. Dmitry, a 41-year-old worker from Samara, says, ‘When I see these annoying advertisements with promises of astronomical payments, I hold back from laughing out loud.’ According to him, in the last two or three months, the rewards for volunteers to be sent to the front have doubled.

Dmitry added, ‘This tells me that the government can’t mobilize anyone and only tempts people with money.’ He added, ‘It’s interesting to know whether such money actually reaches these volunteers or not. From those who have gone to Ukraine, I’ve heard that most of those who went to the front for money were killed very quickly.’