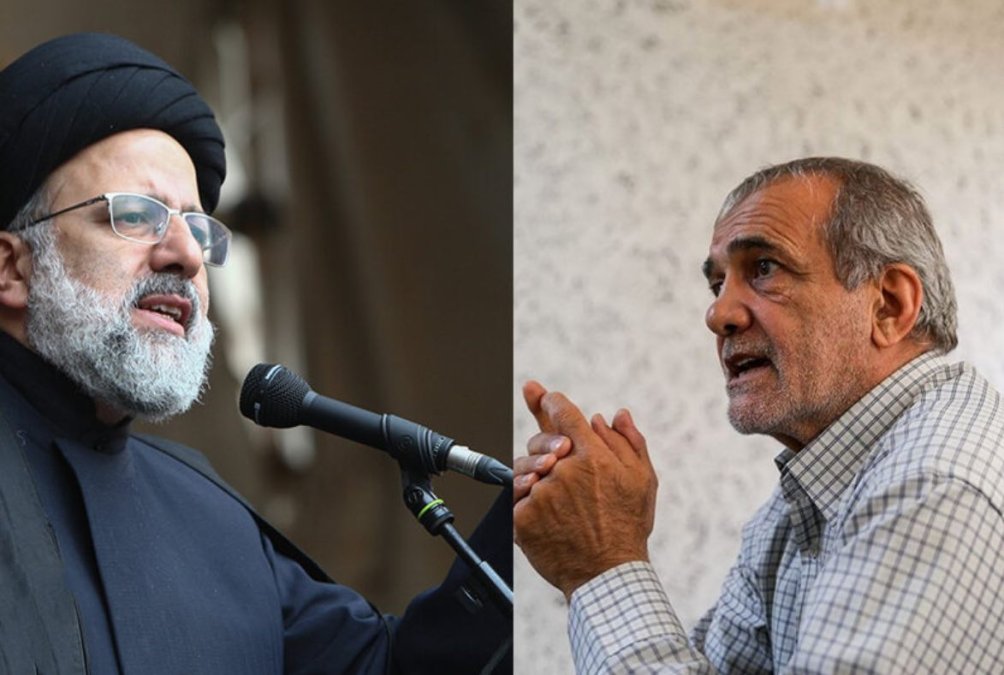

Raisi’s Second Government or the Government of Consensus

Raisi’s Second Government or the Government of Consensus

Abdolnasser Hemmati, the Minister of Economy in the fourteenth government, who was impeached and removed after only 192 days of service, was not a popular figure among conservatives and parliament members from the start. However, his impeachment was a political action against a government that came to power with the slogan of depoliticization. Although Hemmati could not improve the country’s economic situation, the increase in problems and lack of a promising outlook were not solely due to his poor performance. At the same time, it cannot be ignored that Hemmati’s performance was weak. Before Trump signed the executive order for maximum pressure, the wave of price hikes had already started, and the dollar had risen from 59,000 tomans to 84,000 tomans, which was a result of the foreign payment balance deficit, inflationary expectations, and the gap between supply and demand.

The market, overall, reacted positively to Abdolnasser Hemmati’s departure. Hemmati sought shock therapy and the abandonment of interventions by accepting short-term market fluctuations, which did not work. However, his effort to move towards a single exchange rate somewhat closed the door on profiteering and angered those benefiting from strategic and systematic corruption.

Since the main factors of Iran’s structural and chronic economic crisis lie in the realm of political economy, it can be said that Hemmati was sacrificed to shift the blame onto him, allowing the institution of the Supreme Leader to absolve itself of responsibility for a while longer. Meanwhile, the main cause of energy imbalances, high inflation, unemployment, poor performance, and increasing poverty is the macro policies of Ali Khamenei, as the leader of the Islamic Republic, who has sidelined rational administration and conventional bureaucracy within the framework of ideological views and living in a parallel world with reality.

The analogy by Ali Moradi Maraghei, a contemporary historian, is enlightening, comparing Hemmati’s impeachment to the beating of the caretakers of Qajar princes. Back then, any mistake made by the princes, regardless of their caretakers’ fault or innocence, resulted in the punishment of the caretakers. Mohammad Javad Zarif also eventually yielded to the demand of Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the Speaker of Parliament, to resign from the government, although this happened after a meeting with Mohseni Ejei, the head of the judiciary, and possibly due to implicit threats.

Zarif was dismissed without regard for the legal mechanisms within the system, just as his appointment as Deputy Strategic was issued without considering the official law. Zarif had no role in the decision-making and decision-taking of the diplomatic apparatus.

When his views diverged clearly from those of Abbas Araghchi, the Foreign Minister, the position of the institution of the Supreme Leader and the majority of the parliament was clear. The regional and global conditions, along with the Trump administration’s approach, left no room for his continued activity, which seemed from the beginning to be a temporary guest in the fourteenth government.

Ultimately, Zarif and Hemmati were not desirable to the core of power. Their limited reformism and positive view of modern bureaucracy made their loyalty seem unreliable.

The Islamic Republic prefers to use them opportunistically only at specific times and not have them permanently in decision-making circles. The dismissal of Zarif and Hemmati dispelled doubts about the notion that the government of Pezeshkian is Raisi’s second government and has started work as part of a security design to consolidate the mafia-like government’s relations.

Mohammad Javad Zarif’s position in explaining and promoting the national consensus project clearly showed the early failure of this project, which aimed to create reconciliation between the two factions of the government by giving space to forces that accepted the hegemony and leadership of Ali Khamenei. Another goal was to persuade public opinion by strengthening the perception of the government moving away from extremism and towards moderation, distancing from subversive and revolutionary approaches, and hoping in the capacities within the legal framework of the Islamic Republic.

However, the institution of the Supreme Leader aimed to lure people into the system’s desired policies and create illusions, which failed at the first step in the elections. Furthermore, the efforts of Zarif and his close circle, known as the ‘openers’, not only failed to attract more supporters but also could not prevent their decline.

In reality, the expectation of the institution of the Supreme Leader from the claimed consensus was the opposite, meaning discord. From this perspective, when Zarif and his colleagues could not advance the national consensus project, their usefulness ended.

But now, especially with the statements Pezeshkian made in defense of his Economy Minister Hemmati, reiterating that he follows Khamenei in all decisions, including contentious matters, the national consensus has reached its end. Even conservative and compliant reformists do not fit within it, and it is only a gathering place for staunch loyalists.

During the election competition, all the claims of Pezeshkian’s government supporters and carriers were that the hardliners within the government are obstacles, and by building trust with Khamenei and moderating demands, they can be sidelined.

However, this incorrect formulation, which ignored the characteristics of the power structure and the path taken over the past two decades, and hoped for depoliticization, quickly vacated the stage in front of the main source of extremism.

They now stand where Saeed Jalili once stood.

The only difference is that Jalili has complete theoretical alignment with Ali Khamenei’s views and the classic perspectives of the Islamic Republic, while Zarif and Pezeshkian’s team have different, albeit not very extensive, views but in practice submit to Khamenei’s commands and prohibitions. The experience of maximal and minimal reformist approaches in Khatami and Rouhani’s governments taught the majority of Iranians that these two perspectives, despite limited differences, ultimately converge at the same point.

Khamenei resists any meaningful change in macro policies that would lead to the semantic transformation of the system and wants to preserve the current trend as an achievement of his leadership and pass it on to the post-him era.

The first red card the government received from the fourteenth parliament is not a temporary and recoverable defeat but rather illuminates the core security nature of this government and its institutionalized barrenness due to the misguided and delusional strategy it has taken.

In this framework, perhaps Masoud Pezeshkian unwittingly closes the case of election-centric politics in Iran.

With all this said, it seems Pezeshkian personally is happy to be residing in Pasdaran and the results of the government’s performance ultimately do not matter much to him, and he will not be inclined to fulfill the vague promise of resignation if he fails to fulfill his commitments.